The History of the 1951 Refugee Convention

Introduction

When delegates from 26 countries as diverse as the United States, Israel and Iraq gathered in the elegant Swiss city of Geneva in 1951, they had some unfinished business to attend to.

World War II had long since ended, but hundreds of thousands of refugees still wandered aimlessly across the European continent or squatted in makeshift camps.

The international community had, on several occasions earlier in the century, established refugee organizations and approved refugee conventions, but legal protection and assistance remained rudimentary.

After more than three weeks of tough legal wrangling, delegates on 28 July adopted what has become known as the Magna Carta of international refugee law, the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees.

This resulting instrument was a legal compromise “conceived out of enlightened self-interest,” according to one expert. Governments refused to “sign a blank check” against the future, limiting the scope of the Convention mainly to refugees in Europe and to events occurring before 1 January 1951.

It was hoped the ‘refugee crisis’ could be cleared up quickly. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the guardian of the Convention, which had been created shortly before, was given a three-year mandate and was then expected to ‘go out of business’ with the problem solved.

67 years later, the treaty remains a cornerstone of protection. There have been momentous achievements and changes along the way. Regional conventions were created in its image. Some provisions such as the definition of the term ‘refugee’ and the principle of non-forcible return of people to territories where they could face persecution (non-refoulement) have become fundamental international law. With the treaty’s help, UNHCR assisted an estimated 50 million people restart their lives.

The global crisis outgrew parts of the original document and a 1967 Protocol to the Convention eliminated the time constraints. Issues which the original delegates, all males, never even considered such as gender-based persecution became major problems.

This refugee world also became more crowded, with millions of refugees, economic migrants and others on the move. All of this, some critics argue, has made the Convention outdated and irrelevant.

Many jurists say the Convention has shown extraordinary longevity and flexibility in meeting known and unforeseen challenges.

Whatever the outcome of these discussions, it is certain that millions of uprooted people will continue to rely on the Convention for their protection.

A treaty under attack

The images were stark and shocking: in the heart of Europe, tens of thousands of people were fleeing terror and murder, inflicted by their own government, because of their ethnic background.

Men, women and children, bundled in blankets and carrying whatever possessions they could fit into bags or, if they were lucky, broken down carts and rusting tractors, staggered into neighbouring countries in search of safety.

These images were eerily reminiscent of an earlier era, though they were not in the grainy black-and-white of the mid-1940s.

Five decades earlier the international community had faced a similar tragedy in the aftermath of World War II when millions of uprooted peoples wandered hungry and aimlessly through devastated landscapes and cities.

In a spirit of empathy and humanitarianism, and with a hope that such widespread suffering might be averted in the future, nations came together in the stately Swiss city of Geneva and codified binding, international standards for the treatment of refugees and the obligations of countries towards them.

The resultant, ground-breaking, 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees subsequently helped millions of civilians to rebuild their lives and has become “the wall behind which refugees can shelter,” says Erika Feller, director of the Department of International Protection of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). “It is the best we have, at the international level, to temper the behaviour of states”.

But 67 years after its adoption, the Convention is coming apart at the seams, according to some of the same capitals which had breathed life into the protection regime a half century ago.

Crises such as Syria, Myanmar, South Sudan or Yemen have multiplied, spilling millions of people into headlong flight in search of a safe haven. Intercontinental travel has become easy and a burgeoning business in human trafficking has swelled the number of illegal immigrants.

States say their asylum systems are being over-whelmed with this tangled mass of refugees and economic migrants and are urging a legal retrenchment.

The Convention, they say, is outdated, unworkable parties. Where it will all lead remains unclear.

Developing Protection

People have fled persecution from the moment in earliest history when they began forming communities.

A tradition of offering asylum began at almost the same time; and when nations began to develop an international conscience in the early 20th century, efforts to help refugees also went global.

Fridtjof Nansen was appointed in 1921 as the first refugee High Commissioner of the League of Nations, the forerunner of the United Nations.

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency (UNRRA) assisted seven million people during and after the Second World War and a third group, the International Refugee Organization (IRO), and irrelevant.

The High Commissioner, has warned, however, that “many prosperous countries with strong economies complain about the large number of asylum seekers, but offer too little to prevent refugee crises, like investing in conflict prevention, return, reintegration.” In Europe, he said, “It is a real problem that Europeans try to lessen obligations to refugees... In any case, no wall will be high enough to prevent people from coming.

This debate is already taking place within the context of a series of meetings, termed ‘global consultations’, which UN-HCR, as the guardian of the Convention, is holding with the 140 countries that have acceded to the original instrument and a subsequent Protocol, and other interested created in 1946, resettled more than one million displaced Europeans around the world and helped 73,000 civilians to return to their former homes.

A body of refugee law also began to take root. The 1933 League of Nations’ Convention relating to the International Status of Refugees and the 1938 Convention concerning the Status of Refugees coming from Germany provided limited protection for uprooted peoples.

The 1933 instrument, for instance, had introduced the notion that signatory states were obligated not to expel authorized refugees from their territories and to avoid “non-admittance [of refugees] at the frontier.” But that Convention lacked teeth: only eight countries ratified it, several of them after imposing substantial limitations on their obligations.

But none of these early refugee organizations were totally successful, legal protection remained rudimentary and leading members of the newly created United

Nations, formed to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war”, deter-mined that a stronger refugee regime was necessary.

With nearly one million refugees still milling hopelessly around Europe long after the end of the war, UNHCR was created in 1950 and the following year the Refugee Convention, the major legal foundation on which UNHCR’s work is based, was adopted.

The 26 participating countries were heavily western or liberal in orientation, though they were joined by other states such as Iraq, Egypt and Colombia.

Conspicuously absent, with the exception of Yugoslavia, was the Soviet-dominated communist bloc.

For three weeks, in the United Nations European Office overlooking Lake Geneva, delegates hammered out a refugee bill of rights. It involved long and hard bargaining, interminable legal wrangling and a not to expel authorized refugees from their territories and constant eye cocked to protect the rights of sovereign states.

“The modern system of refugee rights was... conceived out of enlightened self-interest,” James C. Hathaway, professor of law and director of the Program in Refugee and Asylum Law at the University of Michigan has written.

One heated debate was sparked over the refusal of some delegates to commit themselves to open-ended legal obligations.

In elaborating one of the Convention’s core definitions—who could be considered a refugee—some countries favoured a general description covering all future refugees.

Others wanted to limit the definition to then existing categories of refugees.

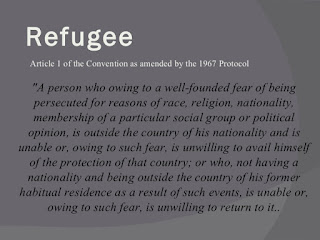

In the end, inevitably, there was a compromise. A general definition emerged, based on a “well-founded fear of persecution” and limited to those who had become refugees “as a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951.”

This temporal limitation—and the option to impose a geographical limitation by interpreting the word ‘events’ to mean either ‘events occurring in Europe’ or ‘events occurring in Europe or elsewhere’—was incorporated because the drafters felt “it would be difficult for governments to sign a blank check and to undertake obligations towards future refugees, the origin and number of which would be unknown”.

Arguably the Convention’s most important provision—the obligation by governments not to expel or return (refouler) an asylum seeker to a territory where he faced persecution—was also fought over at length.

Diplomats questioned whether non-refoulement applied to persons who had not yet entered a country and, thus, whether governments were under any obligation to allow large numbers of persons claiming refugee status to cross their frontiers.

Though the principle of non-refoulement is now generally recognized as so basic it is considered part of customary law, the particular debate continues.

In a controversial 1993 decision, the United States Supreme Court concluded that immigration officials did not strictly contravene the Convention when they seized an repatriated boatloads of Haitian asylum seekers in waters outside U.S. territory. But in the type of intricate legal opinion that might baffle anyone but a lawyer, the Supreme Court also acknowledged that the Convention’s drafters “may not have contemplated that any nation would gather fleeing refugees and return them to the one country they had desperately sought to escape; such actions may even violate the spirit of Article 33”, which for- bids forcible return.

The conference ended on 25 July 1951 and the Convention was formally adopted three days later, but much hard work still lay ahead. There was interminable fine tuning and hard bargaining.

As late as 1959, UNHCR’s representative in Greece cabled Geneva in despair: “I doubt whether I have ever in my life asked so many times the most different persons for one and the same thing as I have pressed in Greece for the ratification of the Convention. Still the prospects are not brilliant.”

In a letter to UNHCR in 1956, India out-lined its domestic refugee concerns and concluded, “In view of this, the government of India do not propose to become a party to the above mentioned Convention for the present.”

India, the second most populous country in the world, has still not acceded to the Convention, though itis, ironically perhaps, a member of UNHCR’s Executive Committee, which helps establish global refugee policy.

Despite the hiccups and hesitations, in December 1952, Denmark became the first country to ratify the Convention. After five additional states—Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Federal Republic of Germany and Australia—had also acceded, the Convention officially came into force on 22 April 1954.

For the first time, there was a global instrument that represented a major improvement on pre-World War II treaties and advanced international law in several important ways.

The 1951 Convention contains a more general definition of the term refugee and it accords them a broader range of rights. Influenced by the 1933 Refugee Convention and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1951 instrument allows refugees the freedom to practice religion and provide religious education to their children, access to courts, elementary education and public assistance.

In the field of housing and jobs, a refugee should be treated at least as favourably as other nationals of a foreign country.

Conversely, the Convention also spelled out the obligations of refugees toward host countries. “Too often, the refugee was far from conforming to the rules of the community,” a French delegate said at the time of the drafting in pushing for such an outline. “Often, too, the refugee exploited the community.”

The instrument stipulated who is not covered by its provisions in its ‘exclusion clause’ (people who commit war crimes, for instance) and when the Convention ceases to apply in its cessation clauses.

For the first time it created a formal link between the treaty and an international agency, UNHCR, which was given authority to supervise its application.

Crucially, more states helped draft the treaty—and have since ratified it—than have supported any other refugee instrument.

Despite its compromises and its limitations “what was done for refugees through the Convention was a major achievement in the humanitarian field,” according to Ivor C. Jackson, who worked for UNHCR for 30 years, including as deputy director of the organization’s Department of International Protection.

A Newphase

The original framers had not expected refugee issues to be a major international problem for very long. UNHCR had been given a limited three-year mandate to help the post-World War II refugees and then, it was hoped, go out of business.

In-stead, the refugee crisis spread, from Europe in the 1950s to Africa in the 1960s and then to Asia and by the 1990s back to Europe.

The Convention obviously needed strengthening to remain relevant for these new waves of exiles. In 1967 the U.N. General Assembly adopted the Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, which effectively removed the earlier 1951 deadline and the geographical restrictions while retaining other main provisions of the instrument.

This was only one response as refugee problems became more complex in the following decades, as the number of people seeking safety swelled from less than one million to a high of more than 27 million in 1995, and as new categories of exiles, such as so-called internally displaced people, were created.

In one innovative and relatively benign approach, some countries resorted to home-grown ‘temporary protection’ arrangements to accommodate large-scale influxes of asylum seekers, such as the hundreds of thousands of civilians who fled Bosnia and, later, Kosovo during the 1990s.

These schemes had both benefits and drawbacks. They allowed civilians to enter a country speedily and with a mini mum of red tape, but since there were no binding universal standards that apply to temporary protection, the rights accorded to asylum seekers were often fewer in number and less generous in scope than those provided for under the Convention.

In addition, beneficiaries were usually granted only ‘temporary’ residence, as the term implies, and governments could end their protection arrangements at their own discretion. Thus temporary protection may be a practical complement to the Convention, but according to UNHCR, it is not, and should not be used as, a substitute for the treaty.

There were also many negative developments. Countries which earlier had welcomed limited numbers of refugees or had accepted large groups for political as well as humanitarian considerations (people fleeing to the West from European communist countries, for instance) began to close their doors. The term ‘Fortress Europe’ was coined.

Inevitably, the Convention came under closer scrutiny and convoluted legal arguments were formulated to try to stem the flow of asylum seekers when politically expedient. Because the 1951 instrument does not define the term ‘persecution’ the definition itself has been subject to wildly differing—and increasingly restrictive—interpretations.

Some capitals argued that the nature of persecution has changed over the past 50 years, and that people who flee civil war, generalized violence or a range of human rights abuses in their home countries, and who usually do so in large numbers, are not fleeing persecution per se.

UNHCR says that war and violence have been used increasingly as instruments of persecution according to the Convention. In conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, the Great Lakes region of Africa and Kosovo, for instance, violence was deliberately used to persecute specific communities; ethnic or religious ‘cleansing’ was the ultimate goal of those conflicts.

The Bad Guys

In 1951, so-called ‘agents of persecution’ were generally assumed to be states. Now, refugees more often flee areas where there is no functioning government, where they are victims of shadowy organizations, rebel movements or local militia.

A few governments insist that actions by these ‘non-state agents’ cannot be considered ‘persecution’ under the Convention. Others reason that if a country tolerates, is complicit in, or cannot prevent persecution by no state agents, then refugee status should be granted to the victims.

Given the Convention’s silence on the issue, UNHCR believes the source of the persecution is less a factor in determining refugee status than whether mistreatment stems from one of the grounds stipulated in the Convention. 6 years ago, the European Court of Human Rights reaffirmed that persecution by non-state agents is still persecution by ruling that returning asylum seekers to situations in which they could face persecution violates the European Convention of Human Rights, whatever the origin of the persecution.

Some states argued that the Convention only applies to individuals (“...the term

‘refugee’ shall apply to any person who...”); therefore, the provisions of the Convention do not apply to large groups of people seeking asylum in a country in masse, which is increasingly the case.

Humanitarian jurists say that nothing in the definition implies that it refers only to individuals and underline that when the Convention was drafted, its intended beneficiaries were, in fact, large groups of people displaced by World War II.

The Convention’s provisions present a complex legal challenge. While some articles are absolute, many are flexible enough to allow the treaty to live and evolve, through interpretation, as times and circumstances change.

Equally, the Convention’s silence on a number of issues, including asylum, gender and burden sharing, has ignited heated debate in recent years among governments, legal scholars and UNHCR.

Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserts the right of persons to seek and enjoy asylum, the Convention makes no mention of such a right, nor of any obligation on countries to admit asylum seekers.

The Convention does protect those refugees who lost, left behind or could not obtain proper documentation and so entered a potential asylum country unlawfully. States are obliged not to impose penalties on those people as long as “they present themselves without delay to the authorities and show good cause for their illegal entry or presence.”

The only reference to states’ responsibilities in admitting refugees appears inthe drafters’ Final Act. They recommended “that Governments continue to receive refugees in their territories and...Act in concert in a true spirit of international cooperation in order that these refugees may find asylum and the possibility of resettlement.

Genderviolence

The Convention doesn’t mention gender in its list of grounds on which refugee status is based, but there is growing recognition that gender-related violence under certain circumstances falls within the refugee definition (see box). In considering a case in 1999, Great Britain’s House of Lords determined that women could be considered “a particular social group “when persecuted because of behaviours or attitudes at odds with prevalent social mores—mores, say, that discriminate against women or accord them less legal protection than men.

While the Convention is predicated on international cooperation and recognizes the need to share equitably the burdens and responsibilities of protecting refugees, it gives no prescription on how to do so.

Burden-sharing has become one of the most contentious issues among receiving countries, one that involves not just people and money but competition for food, medical services, jobs, housing and the environment. Left unresolved, the issue could threaten the very existence of the international refugee protection regime.

The problem of internally displaced persons—people displaced by war and generalized violence but who remain within their home countries—demands urgent action.

This group now numbers between 20 and 25 million in at least 40 countries, compared with an estimated 12 million refugees. Although they may have fled their homes for the same reasons as refugees, because they have not crossed an international border, they still, at least in theory, enjoy the legal protection of their governments and so are not covered by the Refugee Convention. But given the minimal or non-existent protection accorded to most IDPs, the international community has begun considering how best to secure their rights.

The growing tendency among some governments to interpret the Convention’s provisions restrictively is a reaction to the strain imposed on asylum systems by the rise in uncontrolled migration and both real and perceived abuse of those systems.

Cheap international travel and global communications are prompting increasing numbers of people to abandon their homes and to try to improve their lot elsewhere, whether for economic or refugee-related reasons.

Smugglers and traffickers have launched a multi-billion dollar trade in people. Economic migrants and genuine refugees often become hopelessly entangled in the race to reach ‘promised land.’

As the distinction between the two becomes blurred, sometimes intentionally so, the rhetoric against all those perceived as ‘foreigners’ and ‘bogus refugees’ and, increasingly, against the Refugee Convention, itself, has become more barbed.

There is no question that the number of those seeking asylum in developed countries increased substantially over the past two decades. In 2000, just over 400,000 persons applied for asylum in the 15 countries of the European Union (EU), double the number in 1980, but down from a high of 700,000 in 1992. http://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

With the increase in asylum seekers comes an increase in expenditures to pay for refugee status determination procedures and for the social assistance provided to asylum seekers. By one estimate, that expense among developed countries around the world reached $10 billion in 2000. When only one-quarter of asylum seekers is ultimately granted refugee status, as happened in the EU in 1999, governments balk.

Reconsidering the Convention

Lawmakers from Washington to Berlin have worried that the Convention was a convenient screen behind which everyone from terrorists to mass murderers and dope dealers could hide.

Humanitarian lawyers insist that existing provisions are already strong and flexible enough to meet these challenges and already exclude such categories of persons.

Many of the arguments made by critics also miss or disregard a fundamental fact: the Convention was never intended to be a migration control instrument.

“The problem of migration has to be addressed in tandem with the refugee problem, but using different tools. “The Convention can’t be held responsible for failing to deal with situations it was never designed to address.”

It may be open to interpretation, but according to Feller a restrictive reading of the Convention is not the appropriate reaction. “There are provisions in the Convention that could be written better; the letter, the terms have, to some extent, worked against the instrument in today’s world,” she said. “But you cannot interpret international law as though it is domestic legislation. It is in one sense an instrument of compromise, drafted by diplomats. The basis of the Convention is timeless.”

While some governments of developed countries are reading the Convention ever more restrictively, and jeopardizing the safety of genuine refugees in the process, the quality of asylum in developing countries has been steadily deteriorating.

Refugee camps have been attacked, armed militias have been allowed to mingle with, and intimidate, refugees with seeming impunity and civilians, including tens of thousands of children, have been forcibly recruited by the gunmen.

Many developing countries host large numbers of refugees for long periods of time, with ruinous consequences for their already scarce economic and natural resources. Yet, they say, they receive little assistance from the developed world for doing so.

Two countries in southwest Asia, Iran and Pakistan, host twice as many refugees as do all the countries of Western Europe combined. Yet in 2000, the world’s wealthiest nations contributed less than $ billion—one-tenth the amount they spent on maintaining their own asylum systems—to fund UNHCR’s protection work around the world.

Making Protection Work

Balancing the interests of governments with the needs of refugees is difficult but essential. The burden-sharing can never be a pre-condition for meeting responsibilities.

These do, though, need to be rationalized. We have to get together and figure out how to make protection work, and how to keep the Convention central to our work.

UNHCR recently launched its global consultations with governments, legal scholars, non-governmental organizations and refugees themselves, to do just that.

The discussions are designed to reaffirm the commitment of governments to the

Convention, at the same time examining key protection concerns not explicitly addressed in the 1951 instrument.

Much has changed over the past 67 years. The world is more complex than it was in 1951; people are more mobile; shades of gray elude categorization where once black-and-white fitted neatly into hard- won definitions.

Humanitarianism has seemingly been replaced by hard-nosed pragmatism, empathy by suspicion.

But one thing has not changed: people still flee persecution, war and human rights violations and have to seek refuge in other countries. For refugees, the 1951 Convention is the one truly universal, humanitarian treaty that offers some guarantee their rights as human beings will be safe guarded.

Sources consulted:

UNHCR: The Legislation that Underpins our Work.

http://www.unhcr.org/3b5e90ea0.html#_ga=1.119417290.250873371.1455296137

Migration Policy Institute by Elizabeth Collet. Director of MPI Europe and Senior Advisor to MPI’s Transatlantic Council on Migration.

http://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/paradox-eu-turkey-refugee-deal

United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law:

http://www.un.org/en/sections/what-we-do/uphold-international-law/index.html

When delegates from 26 countries as diverse as the United States, Israel and Iraq gathered in the elegant Swiss city of Geneva in 1951, they had some unfinished business to attend to.

World War II had long since ended, but hundreds of thousands of refugees still wandered aimlessly across the European continent or squatted in makeshift camps.

The international community had, on several occasions earlier in the century, established refugee organizations and approved refugee conventions, but legal protection and assistance remained rudimentary.

After more than three weeks of tough legal wrangling, delegates on 28 July adopted what has become known as the Magna Carta of international refugee law, the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees.

Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees - unhcr

This resulting instrument was a legal compromise “conceived out of enlightened self-interest,” according to one expert. Governments refused to “sign a blank check” against the future, limiting the scope of the Convention mainly to refugees in Europe and to events occurring before 1 January 1951.

It was hoped the ‘refugee crisis’ could be cleared up quickly. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the guardian of the Convention, which had been created shortly before, was given a three-year mandate and was then expected to ‘go out of business’ with the problem solved.

67 years later, the treaty remains a cornerstone of protection. There have been momentous achievements and changes along the way. Regional conventions were created in its image. Some provisions such as the definition of the term ‘refugee’ and the principle of non-forcible return of people to territories where they could face persecution (non-refoulement) have become fundamental international law. With the treaty’s help, UNHCR assisted an estimated 50 million people restart their lives.

The global crisis outgrew parts of the original document and a 1967 Protocol to the Convention eliminated the time constraints. Issues which the original delegates, all males, never even considered such as gender-based persecution became major problems.

This refugee world also became more crowded, with millions of refugees, economic migrants and others on the move. All of this, some critics argue, has made the Convention outdated and irrelevant.

Many jurists say the Convention has shown extraordinary longevity and flexibility in meeting known and unforeseen challenges.

Whatever the outcome of these discussions, it is certain that millions of uprooted people will continue to rely on the Convention for their protection.

A treaty under attack

The images were stark and shocking: in the heart of Europe, tens of thousands of people were fleeing terror and murder, inflicted by their own government, because of their ethnic background.

Men, women and children, bundled in blankets and carrying whatever possessions they could fit into bags or, if they were lucky, broken down carts and rusting tractors, staggered into neighbouring countries in search of safety.

These images were eerily reminiscent of an earlier era, though they were not in the grainy black-and-white of the mid-1940s.

Five decades earlier the international community had faced a similar tragedy in the aftermath of World War II when millions of uprooted peoples wandered hungry and aimlessly through devastated landscapes and cities.

In a spirit of empathy and humanitarianism, and with a hope that such widespread suffering might be averted in the future, nations came together in the stately Swiss city of Geneva and codified binding, international standards for the treatment of refugees and the obligations of countries towards them.

The resultant, ground-breaking, 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees subsequently helped millions of civilians to rebuild their lives and has become “the wall behind which refugees can shelter,” says Erika Feller, director of the Department of International Protection of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). “It is the best we have, at the international level, to temper the behaviour of states”.

But 67 years after its adoption, the Convention is coming apart at the seams, according to some of the same capitals which had breathed life into the protection regime a half century ago.

Crises such as Syria, Myanmar, South Sudan or Yemen have multiplied, spilling millions of people into headlong flight in search of a safe haven. Intercontinental travel has become easy and a burgeoning business in human trafficking has swelled the number of illegal immigrants.

States say their asylum systems are being over-whelmed with this tangled mass of refugees and economic migrants and are urging a legal retrenchment.

The Convention, they say, is outdated, unworkable parties. Where it will all lead remains unclear.

Developing Protection

People have fled persecution from the moment in earliest history when they began forming communities.

A tradition of offering asylum began at almost the same time; and when nations began to develop an international conscience in the early 20th century, efforts to help refugees also went global.

Fridtjof Nansen was appointed in 1921 as the first refugee High Commissioner of the League of Nations, the forerunner of the United Nations.

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency (UNRRA) assisted seven million people during and after the Second World War and a third group, the International Refugee Organization (IRO), and irrelevant.

The High Commissioner, has warned, however, that “many prosperous countries with strong economies complain about the large number of asylum seekers, but offer too little to prevent refugee crises, like investing in conflict prevention, return, reintegration.” In Europe, he said, “It is a real problem that Europeans try to lessen obligations to refugees... In any case, no wall will be high enough to prevent people from coming.

This debate is already taking place within the context of a series of meetings, termed ‘global consultations’, which UN-HCR, as the guardian of the Convention, is holding with the 140 countries that have acceded to the original instrument and a subsequent Protocol, and other interested created in 1946, resettled more than one million displaced Europeans around the world and helped 73,000 civilians to return to their former homes.

A body of refugee law also began to take root. The 1933 League of Nations’ Convention relating to the International Status of Refugees and the 1938 Convention concerning the Status of Refugees coming from Germany provided limited protection for uprooted peoples.

The 1933 instrument, for instance, had introduced the notion that signatory states were obligated not to expel authorized refugees from their territories and to avoid “non-admittance [of refugees] at the frontier.” But that Convention lacked teeth: only eight countries ratified it, several of them after imposing substantial limitations on their obligations.

But none of these early refugee organizations were totally successful, legal protection remained rudimentary and leading members of the newly created United

Nations, formed to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war”, deter-mined that a stronger refugee regime was necessary.

With nearly one million refugees still milling hopelessly around Europe long after the end of the war, UNHCR was created in 1950 and the following year the Refugee Convention, the major legal foundation on which UNHCR’s work is based, was adopted.

The 26 participating countries were heavily western or liberal in orientation, though they were joined by other states such as Iraq, Egypt and Colombia.

Conspicuously absent, with the exception of Yugoslavia, was the Soviet-dominated communist bloc.

For three weeks, in the United Nations European Office overlooking Lake Geneva, delegates hammered out a refugee bill of rights. It involved long and hard bargaining, interminable legal wrangling and a not to expel authorized refugees from their territories and constant eye cocked to protect the rights of sovereign states.

“The modern system of refugee rights was... conceived out of enlightened self-interest,” James C. Hathaway, professor of law and director of the Program in Refugee and Asylum Law at the University of Michigan has written.

One heated debate was sparked over the refusal of some delegates to commit themselves to open-ended legal obligations.

In elaborating one of the Convention’s core definitions—who could be considered a refugee—some countries favoured a general description covering all future refugees.

Others wanted to limit the definition to then existing categories of refugees.

In the end, inevitably, there was a compromise. A general definition emerged, based on a “well-founded fear of persecution” and limited to those who had become refugees “as a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951.”

This temporal limitation—and the option to impose a geographical limitation by interpreting the word ‘events’ to mean either ‘events occurring in Europe’ or ‘events occurring in Europe or elsewhere’—was incorporated because the drafters felt “it would be difficult for governments to sign a blank check and to undertake obligations towards future refugees, the origin and number of which would be unknown”.

Arguably the Convention’s most important provision—the obligation by governments not to expel or return (refouler) an asylum seeker to a territory where he faced persecution—was also fought over at length.

Diplomats questioned whether non-refoulement applied to persons who had not yet entered a country and, thus, whether governments were under any obligation to allow large numbers of persons claiming refugee status to cross their frontiers.

Though the principle of non-refoulement is now generally recognized as so basic it is considered part of customary law, the particular debate continues.

In a controversial 1993 decision, the United States Supreme Court concluded that immigration officials did not strictly contravene the Convention when they seized an repatriated boatloads of Haitian asylum seekers in waters outside U.S. territory. But in the type of intricate legal opinion that might baffle anyone but a lawyer, the Supreme Court also acknowledged that the Convention’s drafters “may not have contemplated that any nation would gather fleeing refugees and return them to the one country they had desperately sought to escape; such actions may even violate the spirit of Article 33”, which for- bids forcible return.

The conference ended on 25 July 1951 and the Convention was formally adopted three days later, but much hard work still lay ahead. There was interminable fine tuning and hard bargaining.

As late as 1959, UNHCR’s representative in Greece cabled Geneva in despair: “I doubt whether I have ever in my life asked so many times the most different persons for one and the same thing as I have pressed in Greece for the ratification of the Convention. Still the prospects are not brilliant.”

In a letter to UNHCR in 1956, India out-lined its domestic refugee concerns and concluded, “In view of this, the government of India do not propose to become a party to the above mentioned Convention for the present.”

India, the second most populous country in the world, has still not acceded to the Convention, though itis, ironically perhaps, a member of UNHCR’s Executive Committee, which helps establish global refugee policy.

Despite the hiccups and hesitations, in December 1952, Denmark became the first country to ratify the Convention. After five additional states—Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Federal Republic of Germany and Australia—had also acceded, the Convention officially came into force on 22 April 1954.

For the first time, there was a global instrument that represented a major improvement on pre-World War II treaties and advanced international law in several important ways.

The 1951 Convention contains a more general definition of the term refugee and it accords them a broader range of rights. Influenced by the 1933 Refugee Convention and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1951 instrument allows refugees the freedom to practice religion and provide religious education to their children, access to courts, elementary education and public assistance.

In the field of housing and jobs, a refugee should be treated at least as favourably as other nationals of a foreign country.

Conversely, the Convention also spelled out the obligations of refugees toward host countries. “Too often, the refugee was far from conforming to the rules of the community,” a French delegate said at the time of the drafting in pushing for such an outline. “Often, too, the refugee exploited the community.”

The instrument stipulated who is not covered by its provisions in its ‘exclusion clause’ (people who commit war crimes, for instance) and when the Convention ceases to apply in its cessation clauses.

For the first time it created a formal link between the treaty and an international agency, UNHCR, which was given authority to supervise its application.

Crucially, more states helped draft the treaty—and have since ratified it—than have supported any other refugee instrument.

Despite its compromises and its limitations “what was done for refugees through the Convention was a major achievement in the humanitarian field,” according to Ivor C. Jackson, who worked for UNHCR for 30 years, including as deputy director of the organization’s Department of International Protection.

A Newphase

The original framers had not expected refugee issues to be a major international problem for very long. UNHCR had been given a limited three-year mandate to help the post-World War II refugees and then, it was hoped, go out of business.

In-stead, the refugee crisis spread, from Europe in the 1950s to Africa in the 1960s and then to Asia and by the 1990s back to Europe.

The Convention obviously needed strengthening to remain relevant for these new waves of exiles. In 1967 the U.N. General Assembly adopted the Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees, which effectively removed the earlier 1951 deadline and the geographical restrictions while retaining other main provisions of the instrument.

This was only one response as refugee problems became more complex in the following decades, as the number of people seeking safety swelled from less than one million to a high of more than 27 million in 1995, and as new categories of exiles, such as so-called internally displaced people, were created.

In one innovative and relatively benign approach, some countries resorted to home-grown ‘temporary protection’ arrangements to accommodate large-scale influxes of asylum seekers, such as the hundreds of thousands of civilians who fled Bosnia and, later, Kosovo during the 1990s.

These schemes had both benefits and drawbacks. They allowed civilians to enter a country speedily and with a mini mum of red tape, but since there were no binding universal standards that apply to temporary protection, the rights accorded to asylum seekers were often fewer in number and less generous in scope than those provided for under the Convention.

In addition, beneficiaries were usually granted only ‘temporary’ residence, as the term implies, and governments could end their protection arrangements at their own discretion. Thus temporary protection may be a practical complement to the Convention, but according to UNHCR, it is not, and should not be used as, a substitute for the treaty.

There were also many negative developments. Countries which earlier had welcomed limited numbers of refugees or had accepted large groups for political as well as humanitarian considerations (people fleeing to the West from European communist countries, for instance) began to close their doors. The term ‘Fortress Europe’ was coined.

Inevitably, the Convention came under closer scrutiny and convoluted legal arguments were formulated to try to stem the flow of asylum seekers when politically expedient. Because the 1951 instrument does not define the term ‘persecution’ the definition itself has been subject to wildly differing—and increasingly restrictive—interpretations.

Some capitals argued that the nature of persecution has changed over the past 50 years, and that people who flee civil war, generalized violence or a range of human rights abuses in their home countries, and who usually do so in large numbers, are not fleeing persecution per se.

UNHCR says that war and violence have been used increasingly as instruments of persecution according to the Convention. In conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, the Great Lakes region of Africa and Kosovo, for instance, violence was deliberately used to persecute specific communities; ethnic or religious ‘cleansing’ was the ultimate goal of those conflicts.

The Bad Guys

In 1951, so-called ‘agents of persecution’ were generally assumed to be states. Now, refugees more often flee areas where there is no functioning government, where they are victims of shadowy organizations, rebel movements or local militia.

A few governments insist that actions by these ‘non-state agents’ cannot be considered ‘persecution’ under the Convention. Others reason that if a country tolerates, is complicit in, or cannot prevent persecution by no state agents, then refugee status should be granted to the victims.

Given the Convention’s silence on the issue, UNHCR believes the source of the persecution is less a factor in determining refugee status than whether mistreatment stems from one of the grounds stipulated in the Convention. 6 years ago, the European Court of Human Rights reaffirmed that persecution by non-state agents is still persecution by ruling that returning asylum seekers to situations in which they could face persecution violates the European Convention of Human Rights, whatever the origin of the persecution.

Some states argued that the Convention only applies to individuals (“...the term

‘refugee’ shall apply to any person who...”); therefore, the provisions of the Convention do not apply to large groups of people seeking asylum in a country in masse, which is increasingly the case.

Humanitarian jurists say that nothing in the definition implies that it refers only to individuals and underline that when the Convention was drafted, its intended beneficiaries were, in fact, large groups of people displaced by World War II.

The Convention’s provisions present a complex legal challenge. While some articles are absolute, many are flexible enough to allow the treaty to live and evolve, through interpretation, as times and circumstances change.

Equally, the Convention’s silence on a number of issues, including asylum, gender and burden sharing, has ignited heated debate in recent years among governments, legal scholars and UNHCR.

Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserts the right of persons to seek and enjoy asylum, the Convention makes no mention of such a right, nor of any obligation on countries to admit asylum seekers.

The Convention does protect those refugees who lost, left behind or could not obtain proper documentation and so entered a potential asylum country unlawfully. States are obliged not to impose penalties on those people as long as “they present themselves without delay to the authorities and show good cause for their illegal entry or presence.”

The only reference to states’ responsibilities in admitting refugees appears inthe drafters’ Final Act. They recommended “that Governments continue to receive refugees in their territories and...Act in concert in a true spirit of international cooperation in order that these refugees may find asylum and the possibility of resettlement.

Genderviolence

The Convention doesn’t mention gender in its list of grounds on which refugee status is based, but there is growing recognition that gender-related violence under certain circumstances falls within the refugee definition (see box). In considering a case in 1999, Great Britain’s House of Lords determined that women could be considered “a particular social group “when persecuted because of behaviours or attitudes at odds with prevalent social mores—mores, say, that discriminate against women or accord them less legal protection than men.

While the Convention is predicated on international cooperation and recognizes the need to share equitably the burdens and responsibilities of protecting refugees, it gives no prescription on how to do so.

Burden-sharing has become one of the most contentious issues among receiving countries, one that involves not just people and money but competition for food, medical services, jobs, housing and the environment. Left unresolved, the issue could threaten the very existence of the international refugee protection regime.

The problem of internally displaced persons—people displaced by war and generalized violence but who remain within their home countries—demands urgent action.

This group now numbers between 20 and 25 million in at least 40 countries, compared with an estimated 12 million refugees. Although they may have fled their homes for the same reasons as refugees, because they have not crossed an international border, they still, at least in theory, enjoy the legal protection of their governments and so are not covered by the Refugee Convention. But given the minimal or non-existent protection accorded to most IDPs, the international community has begun considering how best to secure their rights.

The growing tendency among some governments to interpret the Convention’s provisions restrictively is a reaction to the strain imposed on asylum systems by the rise in uncontrolled migration and both real and perceived abuse of those systems.

Cheap international travel and global communications are prompting increasing numbers of people to abandon their homes and to try to improve their lot elsewhere, whether for economic or refugee-related reasons.

Smugglers and traffickers have launched a multi-billion dollar trade in people. Economic migrants and genuine refugees often become hopelessly entangled in the race to reach ‘promised land.’

As the distinction between the two becomes blurred, sometimes intentionally so, the rhetoric against all those perceived as ‘foreigners’ and ‘bogus refugees’ and, increasingly, against the Refugee Convention, itself, has become more barbed.

There is no question that the number of those seeking asylum in developed countries increased substantially over the past two decades. In 2000, just over 400,000 persons applied for asylum in the 15 countries of the European Union (EU), double the number in 1980, but down from a high of 700,000 in 1992. http://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

With the increase in asylum seekers comes an increase in expenditures to pay for refugee status determination procedures and for the social assistance provided to asylum seekers. By one estimate, that expense among developed countries around the world reached $10 billion in 2000. When only one-quarter of asylum seekers is ultimately granted refugee status, as happened in the EU in 1999, governments balk.

Reconsidering the Convention

Lawmakers from Washington to Berlin have worried that the Convention was a convenient screen behind which everyone from terrorists to mass murderers and dope dealers could hide.

Humanitarian lawyers insist that existing provisions are already strong and flexible enough to meet these challenges and already exclude such categories of persons.

Many of the arguments made by critics also miss or disregard a fundamental fact: the Convention was never intended to be a migration control instrument.

“The problem of migration has to be addressed in tandem with the refugee problem, but using different tools. “The Convention can’t be held responsible for failing to deal with situations it was never designed to address.”

It may be open to interpretation, but according to Feller a restrictive reading of the Convention is not the appropriate reaction. “There are provisions in the Convention that could be written better; the letter, the terms have, to some extent, worked against the instrument in today’s world,” she said. “But you cannot interpret international law as though it is domestic legislation. It is in one sense an instrument of compromise, drafted by diplomats. The basis of the Convention is timeless.”

While some governments of developed countries are reading the Convention ever more restrictively, and jeopardizing the safety of genuine refugees in the process, the quality of asylum in developing countries has been steadily deteriorating.

Refugee camps have been attacked, armed militias have been allowed to mingle with, and intimidate, refugees with seeming impunity and civilians, including tens of thousands of children, have been forcibly recruited by the gunmen.

Many developing countries host large numbers of refugees for long periods of time, with ruinous consequences for their already scarce economic and natural resources. Yet, they say, they receive little assistance from the developed world for doing so.

Two countries in southwest Asia, Iran and Pakistan, host twice as many refugees as do all the countries of Western Europe combined. Yet in 2000, the world’s wealthiest nations contributed less than $ billion—one-tenth the amount they spent on maintaining their own asylum systems—to fund UNHCR’s protection work around the world.

Making Protection Work

Balancing the interests of governments with the needs of refugees is difficult but essential. The burden-sharing can never be a pre-condition for meeting responsibilities.

These do, though, need to be rationalized. We have to get together and figure out how to make protection work, and how to keep the Convention central to our work.

UNHCR recently launched its global consultations with governments, legal scholars, non-governmental organizations and refugees themselves, to do just that.

The discussions are designed to reaffirm the commitment of governments to the

Convention, at the same time examining key protection concerns not explicitly addressed in the 1951 instrument.

Much has changed over the past 67 years. The world is more complex than it was in 1951; people are more mobile; shades of gray elude categorization where once black-and-white fitted neatly into hard- won definitions.

Humanitarianism has seemingly been replaced by hard-nosed pragmatism, empathy by suspicion.

But one thing has not changed: people still flee persecution, war and human rights violations and have to seek refuge in other countries. For refugees, the 1951 Convention is the one truly universal, humanitarian treaty that offers some guarantee their rights as human beings will be safe guarded.

Sources consulted:

UNHCR: The Legislation that Underpins our Work.

http://www.unhcr.org/3b5e90ea0.html#_ga=1.119417290.250873371.1455296137

Migration Policy Institute by Elizabeth Collet. Director of MPI Europe and Senior Advisor to MPI’s Transatlantic Council on Migration.

http://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/paradox-eu-turkey-refugee-deal

United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law:

http://www.un.org/en/sections/what-we-do/uphold-international-law/index.html

Comments

Post a Comment