HISTORY OF THE UNITED NATIONS CHARTER

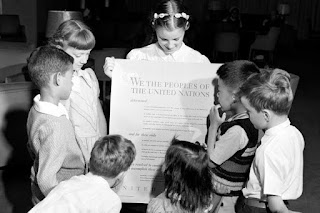

On October 24, 1945 the United

Nations officially comes into existence.

In 1945, representatives of 50

countries met in San Francisco at the United Nations conference on

international organization to draw up the United Nations charter. Those

delegates deliberated on the basis of proposals worked out by the

representatives of china, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United

States at Dumbarton oaks, United States in august-October 1944.

Before the United Nations was established, there was the League

of Nations. Near the end of World War I, President Woodrow Wilson addressed

Congress on January 8th, 1918 and unveiled the steps he felt were

necessary for securing peace, the Fourteen Point

Plan. Part of the fourteen point plan was the creation of the League

of Nations:

A general association of nations must be formed

under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of

political independence and territorial integrity to great and small States

alike.

The League of Nations was

established in 1919 under the Treaty of Versailles.

The League of Nations was established at the end of World

War I as an international peacekeeping organization.

Although US President Woodrow Wilson was an enthusiastic

proponent of the League, the United States did not officially join the League

of Nations due to opposition from isolationists in Congress.

The League of Nations effectively resolved some

international conflicts but failed to prevent the outbreak of the Second World

War.

The

experience of the First World War

World War I was the most destructive conflict in human

history, fought in brutal trench warfare conditions and claiming millions of

casualties on all sides. The industrial and technological sophistication of

weapons created a deadly efficiency of mass slaughter. The nature of the war

was thus one of attrition, with each side attempting to wear the other down

through a prolonged series of small-scale attacks that frequently resulted in

stalemate.

Though the origins of the war were incredibly complex, and

scholars still debate which factors were most influential in provoking the

conflict, the structure of the European alliance system played a significant role.

This system had effectively divided Europe into two camps, based on treaties

that obligated countries to go to war on behalf of their allies.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, American and

European leaders gathered in Paris to debate and implement far-reaching changes

to the pattern of international relations. The League of Nations was seen as

the epitome of a new world order based on mutual cooperation and the peaceful

resolution of international conflicts.

The

establishment of the League of Nations

The Treaty of Versailles was negotiated at the Paris Peace

Conference of 1919, and included a covenant establishing the League of Nations,

which convened its first council meeting on January 16, 1920.

The League was composed of a General Assembly, which

included delegations from all member states, a permanent secretariat that

oversaw administrative functions, and an Executive Council, the membership of

which was restricted to the great powers. The Council consisted of four

permanent members (Great Britain, France, Japan, and Italy) and four

non-permanent members. At its largest, the League of Nations was comprised of

58 member-states. The Soviet Union joined in 1934 but was expelled in 1939 for

invading Finland.

Members of the League of Nations were required to respect

the territorial integrity and sovereignty of all other nation-states and to

disavow the use or threat of military force as a means of resolving international

conflicts. The League sought to peacefully resolve territorial disputes between

members and was in some cases highly effective. For instance, in 1926 the

League negotiated a peaceful outcome to the conflict between Iraq and Turkey

over the province of Mosul, and in the early 1930s successfully mediated a

resolution to the border dispute between Colombia and Peru.

However, the League ultimately failed to prevent the

outbreak of the Second World War, and has therefore been viewed by historians

as a largely weak, ineffective, and essentially powerless organization. Not

only did the League lack effective enforcement mechanisms, but many countries

refused to join and were therefore not bound to respect the rules and

obligations of membership.

The

United States and the League of Nations

US President Woodrow Wilson enunciated the Fourteen Points

in January 1918. The Fourteen Points laid out a comprehensive vision for the

transformation of world politics. Wilson believed that affairs between nations

should be conducted in the open, on the basis of sovereignty,

self-determination (the idea that all nations have the right to choose their

own political identity without external interference), and the disavowal of

military force to settle disputes. Wilson’s vision for the post-war world was

hugely influential in the founding of the League of Nations

President Wilson’s intense lobbying efforts on behalf of US

membership in the League of Nations met with firm opposition from isolationist

members of Congress, particularly Republican Senators William Borah and Henry

Cabot Lodge. They objected most vociferously to Article X of the League’s

Covenant, which required all members of the League to assist any member

threatened by external aggression. In effect, Article X would commit the United

States to defending any member of the League in the event of an attack.

Isolationists in Congress were opposed to any further US involvement in

international conflicts and viewed Article X as a direct violation of US

sovereignty. As a result, the Senate refused to ratify the treaty, and the

United States never became a member of the League of Nations.

Though the League had failed to prevent the outbreak of

another world war, it continued to operate until 1946, when it was formally

liquidated. By this time, the Allied powers had already begun to discuss the

creation of a new successor organization, the United Nations. The United

Nations, which is still in existence today, was based on many of the same

principles as the League of Nations, but was designed specifically to avoid the

League’s major weaknesses. The UN boasts much stronger enforcement mechanisms,

including its own peacekeeping forces, and the membership of the UN is

substantially larger than that of the League even at its peak.

1941:

The Declaration of St. James' Palace

The

sentences from the Declaration of St. James' Palace still serve as the

watchwords of peace: “The only true basis of enduring peace is the willing

cooperation of free peoples in a world in which, relieved of the menace of

aggression, all may enjoy economic and social security; It is our intention to

work together, and with other free peoples, both in war and peace, to this

end.”

In June 1941, London was the home of nine exiled

governments. The great British capital had already seen 22 months of war and in

the bomb-marked city, air-raid sirens wailed all too frequently.

Practically all Europe had fallen to the Axis and ships on

the Atlantic, carrying vital supplies, sank with grim regularity. But in London

itself and among the Allied governments and peoples, faith in ultimate victory

remained unshaken.

And,

even more, people were looking beyond military victory to the postwar future.

“Would

we win only to live in dread of yet another war? Should we not define some

purpose more creative than military victory? Is it not possible to shape a

better life for all countries and peoples and cut the causes of war at their

roots?”

12

June 1941: An Inter-Allied Declaration

On the twelfth of that month the representatives of Great

Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the Union of South Africa and of

the exiled governments of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the

Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Yugoslavia and of General de Gaulle of France, met

at the ancient St. James’ Palace and signed a declaration.

1941:

The Atlantic Charter

Two leaders issued a joint declaration destined to be known

in history as the Atlantic Charter. This document was not a treaty between the

two powers. Nor was it a final and formal expression of peace aims. It was only

an affirmation, as the document declared, “Of certain common principles in the

national policies of their respective countries on which they based their hopes

for a better future for the world.”

Two months after the London Declaration came the next step

to a world organization, the result of a dramatic meeting between President

Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill.

In August 1941, the Axis was still very much in the

ascendant, or so it seemed, and the carefully stage-managed meetings between

Hitler and Mussolini, inevitably ending in “perfect accord,” sounded grimly

foreboding. Germany had flung herself against the USSR but the might of this

new ally was yet to be disclosed. And the United States, though giving moral

and material succor, was not yet in the war.

14

August 1941: A Joint Declaration

Then, one afternoon, came the news that President Roosevelt

and Prime Minister Churchill were in conference “somewhere at sea”—the same

seas on which the desperate Battle of the Atlantic was being fought— and on

August 14 the two leaders issued a joint declaration destined to be known in

history as the Atlantic Charter.

This document was not a treaty between the two powers. Nor

was it a final and formal expression of peace aims. It was only an affirmation,

as the document declared, “Of certain common principles in the national

policies of their respective countries on which they based their hopes for a

better future for the world.”

1942:

Declaration of the United Nations

Representatives of 26 countries fighting the

Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis, decide to affirm their support by Signing the Declaration

by United Nations. This important document pledged the signatory governments to

the maximum war effort and bound them against making a separate peace.

On New Year’s Day 1942,

President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill, Maxim Litvinov, of the USSR, and

T. V. Soong, of China, signed a short document which later came to be known as the United Nations

Declaration. The next day the

representatives of twenty-two other nations added their signatures. This

important document pledged the signatory governments to the maximum war effort

and bound them against making a separate peace.

United Nations

Declaration

The complete

alliance thus effected was in the light of the principles of the Atlantic Charter, and the first clause of the

United Nations Declaration reads that the signatory nations had:

« . . . Subscribed to a common

program of purposes and principles embodied in the Joint Declaration of the

President of the United States of America and the Prime Minister of the United

Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland dated August 14, 1941, known as

the Atlantic Charter ».

Three years later, when

preparations were being made for the San Francisco

Conference, only those states

which had, by March 1945, declared war on Germany and Japan and subscribed to

the United Nations Declaration, were invited to take part.

1943:

Moscow and Teheran Conferences

“We are sure that our concord will win an enduring peace.

We recognize fully the supreme responsibility resting upon us and all the

United Nations to make a peace which will command the goodwill of the

overwhelming mass of the peoples of the world and banish the scourge and terror

of war for many generations.”

By 1943 all the principal Allied nations were committed to

outright victory and, thereafter, to an attempt to create a world in which “men

in all lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.” But the

basis for a world organization had yet to be defined, and such a definition

came at the meeting of the Foreign Ministers of Great Britain, the United

States and the Soviet Union in October 1943.

30

October 1943: Moscow

The United States Secretary

of State, the venerable Cordell Hull, made the first flight of his life to

journey to Moscow for the conference. On October 30, the Moscow Declaration was signed by Vyaches Molotov, Anthony Eden, Cordell

Hull and Foo Ping Shen, the Chinese Ambassador to the Soviet Union.

1

December 1943: Teheran

In December, two months after the four-power Declaration,

Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill, meeting for the first time at Teheran, the

capital of Iran, declared that they had worked out concerted plans for final

victory.

Moscow

Declaration

The Declaration pledged further joint action in dealing

with the enemies’ surrender and, in clause 4, proclaimed:

“That they [the Foreign Ministers] recognize the necessity

of establishing at the earliest practicable date a general international

organization, based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all

peace-loving states, and open to membership by all such states, large and

small, for the maintenance of international peace and security.”

1944-1945: Dumbarton Oaks and Yalta

The Dumbarton

Oaks Conference constituted the first important step taken to carry out

paragraph 4 of the Moscow Declaration of 1943, which recognized the need

for a post-war international organization to succeed the League of Nations.

The principles of the world organization-to-be were thus

laid down. But it is a long step from defining the principles and purpose of

such a body to setting up the structure. A blueprint had to be prepared, and it

had to be accepted by many nations.

7

October 1944: Dumbarton Oaks

For this purpose,

representatives of China, Great Britain, the USSR and the United States met for

a business-like conference at

Dumbarton Oaks, a private mansion

in Washington, D. C. The discussions were completed on October 7, 1944, and a

proposal for the structure of the world organization was submitted by the four

powers to all the United Nations governments and to the peoples of all

countries for their study and discussion.

A

Proposal for the World Organization

1.

Structure

According to the Dumbarton Oaks proposals, four principal

bodies were to constitute the organization to be known as the United Nations.

There was to be a General Assembly composed of all the members. Then came a

Security Council of eleven members. Five of these were to be permanent and the

other six were to be chosen from the remaining members by the General Assembly

to hold office for two years. The third body was an International Court of

Justice, and the fourth a Secretariat. An Economic and Social Council, working

under the authority of the General Assembly, was also provided for.

2.

Roles and Responsibilities

The essence of the plan was that responsibility for

preventing future war should be conferred upon the Security Council. The

General Assembly could study, discuss and make recommendations in order to

promote international cooperation and adjust situations likely to impair

welfare. It could consider problems of cooperation in maintaining peace and

security, and disarmament, in their general principles. But it could not make

recommendations on any matter being considered by the Security Council, and all

questions on which action was necessary had to be referred to the Security

Council.

The actual method of voting in the Security Council -- an

all-important question -- was left open at Dumbarton Oaks for future

discussion.

4.

Armed Forces in the Service of Peace

Another important feature of the Dumbarton Oaks plan was

that member states were to place armed forces at the disposal of the Security

Council in its task of preventing war and suppressing acts of aggression. The

absence of such force, it was generally agreed, had been a fatal weakness in

the older League of Nations machinery for preserving peace.

Yalta

Charter

Leaders of the major allied powers of World War II meeting

at Yalta in the Russian Crimea to decide on military plans for the final defeat

of Germany.

Extensive press and radio discussion enabled people in

Allied countries to judge the merits of the new plan for peace.

Much attention was given to the differences between this

new plan and the Covenant of the League of Nations, it being generally admitted

that putting armed forces at the disposal of the Security Council was a notable

improvement.

11

February 1945: Yalta - the question of voting

One important gap in the

Dumbarton Oaks proposals had yet to be filled: the voting procedure in the

Security Council. This was done at Yalta in the Crimea where Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin,

together with their foreign ministers and chiefs of staff, met in conference.

On February 11, 1945, the conference announced that this question had been

resolved, and it summoned the San Francisco Conference.

“We

are resolved,” the three leaders declared, “upon the earliest possible

establishment with our Allies of a general international organization to

maintain peace and security… “We have agreed that a Conference of United

Nations should be called to meet at San Francisco in the United States on the

25th April, 1945, to prepare the charter of such an organization, along the

lines proposed in the formal conversations of Dumbarton Oaks.”

5

March 1945: San Francisco - an invitation

The invitations were sent out on March 5, 1945, and those

invited were told at the same time about the agreement reached at Yalta on the

voting procedure in the Security Council.

12

April 1945: Change at the Helm

Soon after, in early April, came the sudden death of

President Roosevelt, to whose statesmanship the plans for the San Francisco

Conference owed so much. There was fear for a time that the conference might

have to be postponed, but President Truman decided to carry out all the

arrangements already made, and the conference opened on the appointed date.

1945:

The San Francisco Conference

Forty-six nations, including the four sponsors, were

originally invited to the San Francisco Conference: nations which had declared

war on Germany and Japan and had subscribed to the United Nations Declaration.

One of these nations - Poland - did not send a

representative because the composition of its new government was not announced

until too late for the conference. Therefore, a space was left for the

signature of Poland, one of the original signatories of the United Nations

Declaration. At the time of the conference there was no generally recognized

Polish Government, but on June 28, such a government was announced and on

October 15, 1945 Poland signed the Charter, thus becoming one of the original

Members.

Fifty

Nations, Soon to Be United

The conference itself invited four other states - the

Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist

Republic, newly-liberated Denmark and Argentina. Thus delegates of fifty

nations in all, gathered at the City of the Golden Gate, representatives of

over eighty per cent of the world's population, people of every race, religion

and continent; all determined to set up an organization which would preserve

peace and help build a better world. They had before them the Dumbarton Oaks

proposals as the agenda for the conference and, working on this basis, they had

to produce a Charter acceptable to all the countries.

Delegations

and Staff Number 3,500

There were 850 delegates, and their advisers and staff

together with the conference secretariat brought the total to 3,500. In

addition, there were more than 2,500 press, radio and newsreel representatives

and observers from many societies and organizations. In all, the San Francisco

Conference was not only one of the most important in history but, perhaps, the

largest international gathering ever to take place. The heads of the

delegations of the sponsoring countries took turns as chairman of the plenary meetings:

Anthony Eden, of Britain, Edward Stettinius, of the United States, T. V. Soong,

of China, and Vyacheslav Molotov, of the Soviet Union. At the later meetings,

Lord Halifax deputized for Mr. Eden, V. K. Wellington Koo for T. V. Soong, and

Mr Gromyko for Mr. Molotov.

Plenary meetings are, however, only the final stages at

such conferences. A great deal of work has to be done in preparatory committees

before a proposition reaches the full gathering in the form in which it should

be voted upon. And the voting procedure at San Francisco was important. Every

part of the Charter had to be and was passed by a two-thirds majority.

This is the way in which the San Francisco Conference got

through its monumental work in exactly two months.

One

Charter, Four Sections

The conference formed a "Steering Committee,"

composed of the heads of all the delegations. This committee decided all

matters of major principle and policy. But, even at one member per state, the

committee was 50 strong, too large for detailed work; therefore an Executive

Committee of fourteen heads of delegations was chosen to prepare

recommendations for the Steering Committee.

Then the proposed Charter was divided into four sections,

each of which was considered by a "Commission." Commission one dealt

with the general purposes of the organization, its principles, membership, the

secretariat and the subject of amendments to the Charter. Commission two

considered the powers and responsibilities of the General Assembly, while

Commission three took up the Security Council.

Commission four worked on a draft for the Statute of the

International Court of Justice.

This draft had been prepared by a 44-nation Committee of

Jurists which had met in Washington in April 1945. All this sounds

over-elaborate — especially when the four Commissions subdivided into twelve

technical committees — but actually, it was the speediest way of ensuring the fullest

discussion and securing the last ounce of agreement possible.

Clashes

of Opinion

There were only ten plenary meetings of all the delegates

but nearly 400 meetings of the committees at which every line and comma was

hammered out. It was more than words and phrases, of course that had to be

decided upon. There were many serious clashes of opinion, divergences of

outlook and even a crisis or two, during which some observers feared that the

conference might adjourn without an agreement.

There was the question, for example, of the status of

"regional organizations." Many countries had their own arrangements

for regional defence and mutual assistance. There was the Inter-American

System, for example, and the Arab League. How were such arrangements to be

related to the world organization? The conference decided to give them part in

peaceful settlement and also, in certain circumstances, in enforcement

measures, provided that the aims and acts of these groups accorded with the

aims and purposes of the United Nations.

Treaties

and Trusteeship

The conference finally agreed that treaties made after the

formation of the United Nations should be registered with the Secretariat and

published by it. As to revision, no specific mention was made although such

revision may be recommended by the General Assembly in the course of

investigation of any situation requiring peaceful adjustment.

The conference added a whole new chapter on the subject not

covered by the Dumbarton Oaks proposals: proposals creating a system for

territories placed under United Nations trusteeship. On this matter there was

much debate. Should the aim of trusteeship be defined as

"independence" or "self-government" for the peoples of

these areas? If independence, what about areas too small ever to stand on their

own legs for defence? It was finally recommended that the promotion of the

progressive development of the peoples of trust territories should be directed

toward "independence or self-government."

Debates

and Vetoes

There was also considerable debate on the jurisdiction of

the International Court of Justice and the conference decided that member

nations would not be compelled to accept the Court's jurisdiction but might

voluntarily declare their acceptance of compulsory jurisdiction. Likewise the

question of future amendments to the Charter received much attention and

finally resulted in an agreed solution.

Above all, the right of each of the "Big Five" to

exercise a "veto" on action by the powerful Security Council provoked

long and heated debate. At one stage the conflict of opinion on this question

threatened to break up the conference. The smaller powers feared that when one

of the "Big Five" menaced the peace, the Security Council would be

powerless to act, while in the event of a clash between two powers not

permanent members of the Security Council, the "Big Five" could act

arbitrarily. They strove, therefore, to have the power of the "veto"

reduced. But the great powers unanimously insisted on this provision as vital,

and emphasized that the main responsibility for maintaining world peace would

fall most heavily on them. Eventually the smaller powers conceded the point in

the interest of setting up the world organization.

This and other vital issues were resolved only because

every nation was determined to set up, if not the perfect international

organization, at least the best that could possibly be made.

The Last Meeting

Thus it was that in the Opera House at San Francisco on

June 25, the delegates met in full session for the last meeting. Lord Halifax

presided and put the final draft of the Charter to the meeting. "This

issue upon which we are about to vote," he said, "Is as important as

any we shall ever vote in our lifetime."

In view of the world importance of the occasion, he

suggested that it would be appropriate to depart from the customary method of

voting by a show of hands. Then, as the issue was put, every delegate rose and

remained standing. So did everyone present, the staffs, the press and some 3000

visitors, and the hall resounded to a mighty ovation as the Chairman announced

that the Charter had been passed unanimously.

The

Charter Is Signed

The next day, in the

auditorium of the Veterans' Memorial Hall, the delegates filed up one by one to

a huge round table on which lay the two historic volumes, the Charter and

the Statute of the International Court of Justice. Behind each delegate stood the other members of the

delegation against a colourful semi-circle of the flags of fifty nations. In

the dazzling brilliance of powerful spotlights, each delegate affixed his

signature. To China, first victim of aggression by an Axis power, fell the

honour of signing first.

"The Charter of the United Nations which you have just

signed," said President Truman in addressing the final session, "is a

solid structure upon which we can build a better world. History will honour you

for it. Between the victory in Europe and the final victory, in this most

destructive of all wars, you have won a victory against war itself. . . . With

this Charter the world can begin to look forward to the time when all worthy

human beings may be permitted to live decently as free people."

Then the President pointed out that the Charter would work

only if the peoples of the world were determined to make it work.

"If we fail to use it," he concluded, "we

shall betray all those who have died so that we might meet here in freedom and

safety to create it. If we seek to use it selfishly - for the advantage of any

one nation or any small group of nations — we shall be equally guilty of that

betrayal".

The

Charter Is Approved

The United Nations did not come into existence at the

signing of the Charter. In many countries the Charter had to be approved by

their congresses or parliaments. It had therefore been provided that the

Charter would come into force when the Governments of China, France, Great

Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States and a majority of the other

signatory states had ratified it and deposited notification to this effect with

the State Department of the United States. On October 24, 1945, this condition

was fulfilled and the United Nations came into existence. Four years of

planning and the hope of many years had materialized in an international

organization designed to end war and promote peace, justice and better living

for all mankind.

Bibliography:

The

United Nations: Library of Congress

The

League of Nations: khanacademy

History

of the United Nations: United Nations

Charter

of the United Nations and Statute of the International Court of Justice.

Comments

Post a Comment